Sculpture 1990-2009

Ashet, 1990

Stoneware and coloured slip, 40 cm diameter

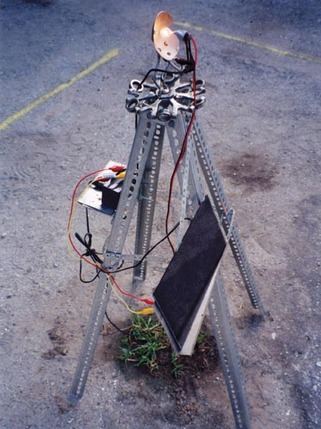

Dark Resistance, 2001

found objects, solar panel, battery, 100 cm x 50 cm

This solar powered sculpture, exhibited outdoors, collected the sun‘s energy during the day to power a light that guided people at night. I feel that it signals the coming of a new age in green technologies. It is ironic that this piece was first built and shown in the Houston Texas in the middle of oil country.

This solar powered sculpture, exhibited outdoors, collected the sun‘s energy during the day to power a light that guided people at night. I feel that it signals the coming of a new age in green technologies. It is ironic that this piece was first built and shown in the Houston Texas in the middle of oil country.

Windsor Plants - January, 2006

This work confronts the trivialized actions of labour within society. It is a critique that postulates that much of aesthetic practice happens when people improve communities by enhancing their homes, property, rental units or gardens. This is work outside of “real work”. What people do outside their workplace has become equated with leisure rather than regarded as an integral component of community life. This is also true of child rearing or cooking and other cultural activities.

This exchange/work exists within the gallery and consist of seeds that I have harvested, in my garden, over the summer. These sunflower seeds are contained within small, 2 1/4” x 3” envelopes, with instructions for planting in the spring and harvesting in the fall. These small envelopes are push-pinned to the wall in a grid format. There is also be a food bank collection receptacle for the participant to donate whatever they can financially. In exchange they can take an envelope containing the 3 sunflower seeds. Removing the pushpin they will show where they intend to plant the seeds in the community indicating this with a pushpin on a map of Windsor provided beside the envelopes.

This work references volunteer labour by examining the food bank, which was/is essential in helping to feed striking workers and the working poor. It further emphasises the value of local knowledge, (planting and harvesting), being traded to enhance life in the community. Unseen or unacknowledged labour = invisible work

This exchange/work exists within the gallery and consist of seeds that I have harvested, in my garden, over the summer. These sunflower seeds are contained within small, 2 1/4” x 3” envelopes, with instructions for planting in the spring and harvesting in the fall. These small envelopes are push-pinned to the wall in a grid format. There is also be a food bank collection receptacle for the participant to donate whatever they can financially. In exchange they can take an envelope containing the 3 sunflower seeds. Removing the pushpin they will show where they intend to plant the seeds in the community indicating this with a pushpin on a map of Windsor provided beside the envelopes.

This work references volunteer labour by examining the food bank, which was/is essential in helping to feed striking workers and the working poor. It further emphasises the value of local knowledge, (planting and harvesting), being traded to enhance life in the community. Unseen or unacknowledged labour = invisible work

A Valley of Ashes

Refuse is a stand-in for refusal, symbolic of discontinuation. Here waste represents the desire to move

“forward,” the desire for “progress” yet also a need for posterity—a preserved thing. The entombed items

within the capsule are frozen in time like a drawing waiting for some future resonating meaning.

In this rendition, the time capsule’s basic shape is modeled on a capsule created by Westinghouse

Electric for the 1939 World’s Fair. Designed to safeguard its contents for 5,000 years, the capsule was

intended to be a record of progress, a representation of the desires, expectations and values of the dominant

culture that created it. The capsule was stored in, what may be regarded as, a mausoleum of modernist and

capitalist aspirations. To keep it from getting from getting lost, Westinghouse distributed an archival book

to thousands of libraries around the world. Entitled The Book of Record, the volume describes the time

capsule, its contents, and its purpose, explaining its location, how to build a metal detector to find it, how to

dig it up, how to open it, and how to decipher the English of five thousand years previous. Central to its

creation is a sense of dystopia, the fear that some future event will negate its existence, so that, a pessimism

persists, in the optimistic act of its creation.

Ironically, the vessel of posterity was buried in a part of New York City now known as Flushing

Meadows Park, home to the 1939 and 1964 World’s Fairs; the site was created from the City’s former

dumping grounds. Originally known as the Corona Ash Dumps, it was popularized as “a valley of ashes” in

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. The site is currently the home of the Queens Museum of Art,

creating an interesting juxtaposition—its silent partner standing idle with caretaker in absentia.

It is doubtful that the modernist agenda, to perfect progress and production, could have been

ignorant of the inevitable dross it would create in its wake. The monumental subterranean wastelands and

pervasive poisons of the present are “the other” of its consumptive free market economy. The presentation

of this work is the antithesis of preservation. It fails as a document and as a time capsule, and like so many

other mass-produced items; the work is made to break. Its obsolescence planned like so many consumer

products in our society. The time capsule’s shape, both phallic and militaristic, frames the digital remnants

of a recording reclaimed while rummaging through a local recycling depot. The recording, “Musical

Masterworks of the 20th Century,” survived being run over, several times, by a truck loader as it went

about its sorting. Finding it led me to re-evaluate its content and reassess its cultural value.

Thus the recording is a marker for the inevitability of the defunct productions of the past, suggesting too the

disposability of culture itself.

“forward,” the desire for “progress” yet also a need for posterity—a preserved thing. The entombed items

within the capsule are frozen in time like a drawing waiting for some future resonating meaning.

In this rendition, the time capsule’s basic shape is modeled on a capsule created by Westinghouse

Electric for the 1939 World’s Fair. Designed to safeguard its contents for 5,000 years, the capsule was

intended to be a record of progress, a representation of the desires, expectations and values of the dominant

culture that created it. The capsule was stored in, what may be regarded as, a mausoleum of modernist and

capitalist aspirations. To keep it from getting from getting lost, Westinghouse distributed an archival book

to thousands of libraries around the world. Entitled The Book of Record, the volume describes the time

capsule, its contents, and its purpose, explaining its location, how to build a metal detector to find it, how to

dig it up, how to open it, and how to decipher the English of five thousand years previous. Central to its

creation is a sense of dystopia, the fear that some future event will negate its existence, so that, a pessimism

persists, in the optimistic act of its creation.

Ironically, the vessel of posterity was buried in a part of New York City now known as Flushing

Meadows Park, home to the 1939 and 1964 World’s Fairs; the site was created from the City’s former

dumping grounds. Originally known as the Corona Ash Dumps, it was popularized as “a valley of ashes” in

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. The site is currently the home of the Queens Museum of Art,

creating an interesting juxtaposition—its silent partner standing idle with caretaker in absentia.

It is doubtful that the modernist agenda, to perfect progress and production, could have been

ignorant of the inevitable dross it would create in its wake. The monumental subterranean wastelands and

pervasive poisons of the present are “the other” of its consumptive free market economy. The presentation

of this work is the antithesis of preservation. It fails as a document and as a time capsule, and like so many

other mass-produced items; the work is made to break. Its obsolescence planned like so many consumer

products in our society. The time capsule’s shape, both phallic and militaristic, frames the digital remnants

of a recording reclaimed while rummaging through a local recycling depot. The recording, “Musical

Masterworks of the 20th Century,” survived being run over, several times, by a truck loader as it went

about its sorting. Finding it led me to re-evaluate its content and reassess its cultural value.

Thus the recording is a marker for the inevitability of the defunct productions of the past, suggesting too the

disposability of culture itself.

Detrituscope - 2007-2008

rivets, P.E.T. plastic, CD player, amplifier, speaker, box tape dimensions variable

Detrituscope is a piece based on statistics from the Basil Convention. The Convention was set up in 1989 and is principally devoted to setting up a framework for controlling the “transboundary” movements of hazardous wastes, across international frontiers especially waste that flows from “developed” to “developing” countries. Even with 170 signatories to the convention, it is fraught with problems some of which include:

• the difficulties in the reporting process

• reporting failures from OECD countries

• jurisdictional disagreements at various levels between countries and the convention

• secretive dumping arrangements that circumvent the conventions ability to track hazardous waste

• the definition of what constitutes hazardous waste differs from state to state • established agreements, such as NAFTA, often trump the convention

The silence in the audio piece mirrors the silence of missing reports and gaps in the process of tracking movements, of what is deemed hazardous waste.

Military Models, 2008

Rivets, Discarded P.E.T. plastic, aluminum tripods

Borrowing materials from previous experience these works are constructed to mimic the process of using repurposed military technologies to heal damaged parts of the environment. Just as Spitfires and other planes were used after WW2 as crop dusters or civilian liners became hospital ships these models shift there mode of operation. By adapting the drone floatplane, destroyer, drone-copter to these scenarios I attempt to create something that would propose alternatively more productive uses of technology to perform different operations these include, seed-bombing, geological surveys, or cleaning the Pacific gyre. An animated video of a virtual drone model can be found here...https://vimeo.com/103058065

Borrowing materials from previous experience these works are constructed to mimic the process of using repurposed military technologies to heal damaged parts of the environment. Just as Spitfires and other planes were used after WW2 as crop dusters or civilian liners became hospital ships these models shift there mode of operation. By adapting the drone floatplane, destroyer, drone-copter to these scenarios I attempt to create something that would propose alternatively more productive uses of technology to perform different operations these include, seed-bombing, geological surveys, or cleaning the Pacific gyre. An animated video of a virtual drone model can be found here...https://vimeo.com/103058065

Destroyer/Creator, 2008

Cast-off P.E.T. plastic, “military grade” glue

Monument to the Sixth International - Model, 2008

Staples, solder, wire, pins

Fog Factory Model, 2006

Cardboard, tape, plasitc, tinfoil, catfood cans